Paul Keating

| The Honourable Paul Keating |

|

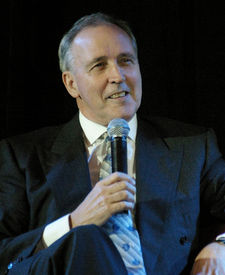

Keating in 2007 |

|

|

24th Prime Minister of Australia

Elections: 1993, 1996 |

|

|---|---|

| In office 20 December 1991 – 11 March 1996 |

|

| Deputy | Brian Howe (1991-1995) Kim Beazley (1995-1996) |

| Preceded by | Bob Hawke |

| Succeeded by | John Howard |

|

Deputy Prime Minister of Australia

|

|

| In office 4 April 1990 – 3 June 1991 |

|

| Prime Minister | Bob Hawke |

| Preceded by | Lionel Bowen |

| Succeeded by | Brian Howe |

|

30th Treasurer of Australia

|

|

| In office 11 March 1983 – 3 June 1991 |

|

| Prime Minister | Bob Hawke |

| Preceded by | John Howard |

| Succeeded by | Bob Hawke[1] |

|

Member of the Australian Parliament

for Blaxland |

|

| In office 25 October 1969 – 15 June 1996 |

|

| Preceded by | James Harrison |

| Succeeded by | Michael Hatton |

|

|

|

| Born | 18 January 1944 Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Political party | Australian Labor Party |

| Occupation | Trade union staffer |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Paul John Keating (born 18 January 1944) is a former Australian politician, and was the 24th Prime Minister of Australia, serving from 1991 to 1996. Keating was elected as the federal Labor member for Blaxland in 1969 and came to prominence as the reformist treasurer when the Hawke Labor government came to power at the 1983 federal election. After becoming prime minister in 1991, he led Labor to its fifth consecutive victory in the 1993 federal election against the Liberal/National coalition led by John Hewson. Many had considered this election unwinnable for Labor, mainly due to the effects that the early 1990s recession had on Australia, as well as the longevity of Labor as the federal government. However, the Labor Party was decisively defeated at the 1996 federal election by the Liberal/National coalition led by John Howard.

Contents |

Early life

Keating grew up in Bankstown, a working-class suburb of Sydney. He was one of four children of Matthew Keating, a boilermaker and trade-union representative of Irish-Catholic descent, and his wife, Minnie. In the 1960s Keating managed ‘The Ramrods’ rock band.[2] Keating was educated at Catholic schools; he was the first practising Catholic Labor prime minister since James Scullin left office in 1932. Leaving De La Salle College Bankstown (now LaSalle Catholic College) at 15, Keating worked as a clerk at the Electricity Commission of New South Wales and then as a research assistant for a trade union. He did not undertake any tertiary education. He joined the Labor Party as soon as he was eligible. In 1966, he became president of the ALP’s Youth Council.[3]

Entry into politics

Through the unions and the NSW Young Labor Council, Keating met other Labor figures such as Laurie Brereton, Graham Richardson and Bob Carr. He also developed a friendship and discussed politics with former New South Wales Labor premier Jack Lang, then in his 90s. In 1971, he succeeded in having Lang re-admitted to the Labor Party.[4] Using his extensive contacts Keating gained Labor endorsement for the federal seat of Blaxland in the western suburbs of Sydney and was elected to the House of Representatives at the 1969 election when he was 25 years of age.[3]

Keating was a backbencher for most of the tenure of the Whitlam Government (December 1972–November 1975), and briefly became Minister for Northern Australia in October 1975. After Labor's defeat in 1975, Keating became an opposition frontbencher and, in 1981, he became president of the New South Wales branch of the party and thus leader of the dominant right-wing faction. As opposition spokesperson on energy, his parliamentary style was that of an aggressive debater. He initially supported Bill Hayden against Bob Hawke's leadership challenges, partly because he hoped to succeed Hayden himself.[5] However, by July 1982, as the leader of the New South Wales right-wing faction, he had to accept, at least nominally, his own faction's endorsement of Hawke's challenge. The formal announcement by Keating, as the faction leader, was actually penned by Gareth Evans.[6]

Treasurer: 1983-1991

Following the Labor Party's victory in the March 1983 election, Keating was appointed treasurer, a post he held until 1991. Keating succeeded John Howard as treasurer and was able to use the size of the budget deficit that had been left by the outgoing government to attack the former treasurer, and question the economic credibility of the Liberal-National Party. That the deficit had significantly blown out in the lead up to the election was not disclosed by the Liberal-National Party government.[7] The incoming Hawke Labor government only learned about the extent of the deficit when briefed by Treasury officials after the election. According to Bob Hawke, the historically large $9.6 billion budget deficit left by the Coalition ‘became a stick with which we were justifiably able to beat the Liberal National Party Opposition for many years’.[7] Although, as the former treasurer, Howard was ‘discredited’[8] by the budget blowout, he had argued unsuccessfully against Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, that the revised figures should be disclosed before the election.[9]

Keating was one of the driving forces behind the various microeconomic reforms of the Hawke government. The Hawke/Keating governments of 1983–1996 pursued economic policies and restructuring such as floating the Australian dollar in 1983, reducing tariffs on imports, taxation reforms, moving from centralised wage-fixing to enterprise bargaining, privatisation of publicly-owned companies such as Qantas and the Commonwealth Bank, and deregulation of the banking system. Keating was instrumental in the introduction of the Prices and Incomes Accord, an agreement between the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) and the government to negotiate wages. His management of the Accord, and close working relationship with ACTU leader Bill Kelty, was a source of tremendous political power for Keating. Keating was able to bypass cabinet in many instances, notably in the exercise of monetary policy.[10]

In 1985, Keating proposed the introduction of a Goods and Services Tax or "GST" (known elsewhere as a value-added tax), which was debated by the party before being dropped by Hawke. The early 1990s recession, which Keating called "the recession we had to have",[11] resulted in significant increase in support for the Liberal party, which Keating used in his push for the Labor party leadership.

Keating's tenure as treasurer and prime minister is often criticised for high interest rates and the 1990s recession. In private, Keating actually argued against interest rate rises during the period, but acquiesced to the recommendations of the public service.[10][12] During the subsequent Howard Government (1996–2007), Keating often criticised Howard for taking credit over the relatively good economic conditions Australia experienced over the latter half of Howard's time as prime minister.[13]

At a 1988 meeting at Kirribilli House, Hawke and Keating discussed the handover of the leadership to Keating. Hawke agreed in front of two witnesses that he would resign in Keating's favour after the 1990 election.[10] The Deputy Prime Minister, Lionel Bowen, retired at the 1990 election, and Keating was appointed Deputy to Hawke. In June 1991, after Hawke had intimated to Keating that he planned to renege on the deal on the basis that Keating had been publicly disloyal and moreover was less popular than Hawke, Keating challenged him for the leadership. He lost (Hawke won 66-44 in the party room ballot),[14] resigned as Treasurer and Deputy Prime Minister, and declared in a press conference that he had fired his 'one shot'.[15] Publicly, at least, this made his leadership ambitions unclear. Having lost the first challenge to Hawke, Keating realised that events would have to move very much in his favour for a second challenge to be even possible.[16]

Several factors contributed to the success of Keating’s second challenge in December 1991. Over the remainder of 1991, the economy showed no signs of recovery from the recession, and unemployment continued to rise.[17][18] Some of Keating’s supporters undermined the government.[17] The Government was polling poorly.[16] Perhaps more significantly, Liberal leader John Hewson introduced Fightback!, an economic policy package, which, according to Keating’s biographer, John Edwards, ‘appeared to astonish and stun Hawke’s cabinet’.[19] According to Edwards, ‘Hawke was unprepared to attack it and responded with windy rhetoric’.[19] After Fightback!, Keating ‘did practically nothing’ as Hawke’s support dwindled and the numbers moved in Keating’s favour.[20]

Prime Minister: 1991–1996

Keating introduced mandatory detention for asylum seekers with bipartisan support in 1992.[21] Mandatory detention was controversial under the Howard Government. On 10 December 1992, Keating delivered a speech on Aboriginal reconciliation, which is considered by many to be one of the great Australian speeches.[22][23][24]

Most commentators believed the 1993 election was "unwinnable" for Labor; the government had been in power for 10 years and the pace of economic recovery from the early 1990s recession was 'weak and slow'.[25] However, Keating succeeded in winning back the electorate with a strong campaign opposing Fightback, memorable for Keating's reference to Hewson's proposed GST as "15% on this, 15% on that", and a focus on creating jobs to reduce unemployment. Keating led Labor to an unexpected election victory, made memorable by his "true believers" victory speech.[26][27] After Keating, some of the reforms of Fightback were implemented under the centre-right coalition government of John Howard, such as the GST.

In December 1993, Keating was involved in a second diplomatic incident with Malaysia, over Keating's description of Dr. Mahathir bin Mohamad as "recalcitrant". The incident occurred after Dr. Mahathir refused to attend the 1993 APEC summit. Keating said, "APEC is bigger than all of us - Australia, the U.S. and Malaysia and Dr. Mahathir and any other recalcitrants." Dr. Mahathir demanded an apology from Keating, and threatened to reduce diplomatic and trade ties with Australia, which became an enormous concern to Australian exporters. Some Malaysian officials talked of launching a "Buy Australian Last" campaign.[28] Keating eventually apologised to Mahathir over the remark.

Keating's agenda included making Australia a republic, reconciliation with Australia's indigenous population, and furthering economic and cultural ties with Asia. The addressing of these issues came to be known as Keating's "big picture."[29] Keating's legislative program included establishing the Australian National Training Authority (ANTA), a review of the Sex Discrimination Act, and native title rights of Australia's indigenous peoples following the "Mabo" High Court decision. He developed bilateral links with Australia's neighbours - he frequently said there was no other country in the world more important to Australia than Indonesia[30] - and took an active role in the establishment of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum (APEC), initiating the annual leaders' meeting. One of Keating's far-reaching legislative achievements was the introduction of a national superannuation scheme, implemented to address low national savings.

Paul Keating's friendship with Indonesian President Suharto was criticised by human rights activists supportive of East Timorese independence and by Nobel Peace Prize winner, José Ramos-Horta (later to be East Timor's prime minister and president). The Keating government's cooperation with the Indonesian military and the signing of the Timor Gap Treaty were also criticised.[31]

Defeat

John Hewson was replaced as Liberal party leader by Alexander Downer in 1994. But Downer's leadership was marred by gaffes, and he was replaced by John Howard in 1995. Under Howard, the Coalition moved ahead of Labor in opinion polls and Keating was unable to wrest back the lead. Labor lost the seat of Canberra in a 1995 by-election. Howard, determined to avoid a repeat of the 1993 election, adopted a "small target" strategy - committing to keep Labor reforms such as Medicare, and defusing the republic issue by promising to hold a constitutional convention. This allowed Howard to focus the election on the economy and memory of the early 1990s recession, and on the longevity of the Labor government, which in 1996 had been in power for 13 years.

In the March 1996 election, the Keating Government was defeated by the Coalition, which scored a 29-seat swing. Keating was the first incumbent Labor Party Prime Minister to lose an election in 46 years, the last being Ben Chifley in 1949.[32] Keating immediately resigned as Labor Party leader, and resigned from Parliament a little over a month later, on 23 April 1996.[33]

After politics

Since leaving parliament, Keating has been a director of various companies,[34] including the Chairman (international) of Carnegie, Wylie & Company, a Sydney based investment bank.[35]

In 1997 Keating declined to accept appointment as a Companion of the Order of Australia. Other than Kevin Rudd, he is the only former post-1975 prime minister not to hold the award since the institution of the Australian Honours System in 1975.[36]

In 2000, he published a book, Engagement: Australia Faces the Asia-Pacific, which focused on foreign policy during his term as prime minister.[37] In March 2002, a Don Watson-authored biography of Keating, Recollections of a Bleeding Heart, was released and has sold over 50,000 copies. It has been awarded the The Age Book of the Year and Best Non-fiction book, The Courier-Mail Book of the Year and the National Biography Award.

During Howard's prime ministership, Keating made occasional speeches strongly criticising his successor's social policies, and defending his own policies, such as those on East Timor. Keating described Howard as a "desiccated coconut" who was "araldited to the seat" and that "Howard ... is an old antediluvian 19th century person who wanted to stomp forever ... on ordinary people's rights to organise themselves at work ... he's a pre-Copernican obscurantist", when criticising the Howard government's WorkChoices policy.[38] He described Howard's deputy, Peter Costello, as being "all tip and no iceberg" when referring to a pact made by Howard to hand the prime ministership over to Costello after two terms.[39] On Labor's victory at the 2007 election, Keating said that he was relieved, rather than happy, that the Howard government had been removed. He claimed that there was "Relief that the nation had put itself back on course. Relief that the toxicity of the Liberal social agenda – the active disparagement of particular classes and groups, that feeling of alienation in your own country – was over."[40]

In May 2007, Keating suggested that Sydney, rather than Canberra, should be the capital of Australia, saying that:

John Howard has already effectively moved the Parliament here. Cabinet meets in Philip Street in Sydney, and when they do go to Canberra, they fly down to the bush capital, and everybody flies out on Friday. There is an air of unreality about Canberra. If Parliament sat in Sydney, they would have a better understanding of the problems being faced by their constituents. These real things are camouflaged from Canberra.[41]

Keating was critical of the then opposition leader (and later prime minister) Kevin Rudd's leadership team. For example, before the 2007 federal election, which Labor won, he criticised the then opposition industrial relations spokesperson Julia Gillard, saying she lacked an understanding of principles such as enterprise-bargaining set under his government in the late 1980s and early 1990s. He also attacked Rudd's chief of staff David Epstein and Gary Gray, who was at that time a candidate for Kim Beazley's seat of Brand, to which he was elected in 2007.[42]

In February 2008, Keating joined former prime ministers Whitlam, Fraser and Hawke in Parliament House, Canberra, to witness the parliamentary apology to the Stolen Generations.[43]

In August 2008, he spoke at the book launch of "Unfinished Business: Paul Keating's Interrupted Revolution", authored by economist David Love. Among the topics discussed during the launch were the need to increase compulsory superannuation contributions, as well as to restore incentives (removed under Howard/Costello) for people to receive their superannuation payments in annuities.[44]

Keating is currently a Visiting Professor of Public Policy at the University of New South Wales. He has been awarded honorary Doctorates in Laws from Keio University in Tokyo, the National University of Singapore, and the University of New South Wales[36]

Personal life

In 1975, Keating married Annita van Iersel, a Dutch flight attendant for Alitalia. The Keatings had four children, who spent some of their teenage years in The Lodge, the Prime Minister's official residence in Canberra. They separated in late November 1998.

Keating's daughter, Katherine, is a former adviser to former New South Wales minister Craig Knowles.[45]

Keating's interests include the music of Gustav Mahler[46] and collecting French antique clocks.[3] He now resides in Potts Point, in the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney.

See also

- First Keating Ministry

- Second Keating Ministry

- Keating! the musical

- Redfern Park Speech

Further reading

- Carew, Edna (1991), Paul Keating Prime Minister, Allen and Unwin.

- Edwards, John (1996), Keating: The Inside Story, Viking.

- Gordon, Michael (1993), A Question of Leadership. Paul Keating. Political Fighter, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland. ISBN 0 7022 2494 4

- Gordon, Michael (1996), A True Believer: Paul Keating, UQP.

- Keating, Paul (1995), Advancing Australia, Big Picture.

- Lowe, David (2008), Unfinished Business: Paul Keating's interrupted revolution, Scribe.

- Watson, Don (2002), Recollections of a Bleeding Heart: A Portrait of Paul Keating, Knopf.

References

- ↑ Hawke held the portfolio for only one day, 3-4 June, 1991 with John Kerin taking on the role from 4 June.

- ↑ "Civicsandcitizenship.edu.au". Civicsandcitizenship.edu.au. http://www.civicsandcitizenship.edu.au/cce/default.asp?id=14942. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Civics | Paul Keating (1944–)". Civicsandcitizenship.edu.au. http://www.civicsandcitizenship.edu.au/cce/default.asp?id=14942. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ↑ "Former PM Paul Keating and historian Frank Cain discuss Jack Lang's life, legacy and the Depression". Abc.net.au. 2005-11-17. http://www.abc.net.au/rn/latenightlive/stories/2005/1509394.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ↑ Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.153

- ↑ Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.159

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hawke, Bob, The Hawke Memoirs, William Heinemann Australia, 1994, p.148

- ↑ Errington, W., & Van Onselen, Peter, John Winston Howard: The Biography, Melbourne University Press, 2007, p.102

- ↑ Errington, W.,& Van Onselen, Peter, John Winston Howard: The Biography, Melbourne University Press, 2007, p.102

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Kelly, Paul. The End of Certainty: Power, Politics, and Business in Australia. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 186373757X. http://books.google.com/books?id=EKXBgmYeO2QC&dq. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ↑ Paul Keating - Chronology at australianpolitics.com

- ↑ "Keating still casts a shadow". Smh.com.au. 2004-08-31. http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2004/08/30/1093852180757.html. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ↑ "Paul Keating on the lead-up to the federal election". Lateline - ABC. 07/06/2007. http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/content/2007/s1945485.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- ↑ Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.435

- ↑ Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.438

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.439

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Hawke, Bob, The Hawke Memoirs, William Heinemann Australia, 1994, p.544

- ↑ Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.440

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.441

- ↑ Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.442

- ↑ Timeline: Mandatory detention in Australia, Special Broadcasting Service, June 17, 2008

- ↑ OPINION Phillip Adams (2007-05-05). "The greatest speech". Theaustralian.news.com.au. http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,20876,21673159-12272,00.html. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ↑ "Keating's Redfern Address voted an unforgettable speech". Cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au. http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/Barani/news/KeatingsRedfernAddressanunforgettablespeech.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ↑ Text of Paul Keating's Redfern Speech

- ↑ Dyster, B., & Meredith, D., Australia in the Global Economy, Cambridge University Press, 1999, p.309

- ↑ Text of the "true believers" victory speech at Wikisource

- ↑ "audio of the "true believers" victory speech". http://australianpolitics.com/sounds/1993/93-03-13_keating-claims-victory.ram. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ↑ Shenon, Philip (1993-12-09). "Malaysia Premier Demands Apology". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F0CE0DB113EF93AA35751C1A965958260. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ↑ Fast Forward, Shaun Carney, The Age, 20-Nov-2007

- ↑ Sheriden, Greg (28 January 2008). "Farewell to Jakarta's Man of Steel". The Australian. http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,25197,23118079-5013460,00.html. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ↑ The World Today - 5/10/99: Howard hits back at Keating over criticism; Australian Jewish Democratic Society - Rabin and East Timor; Microsoft Word - Alpheus Article September#35.doc; ITV - John Pilger - A voice that shames those who are silent on Timor

- ↑ Gough Whitlam was not the incumbent Prime Minister at the time of his defeat in the December 1975 election, as Malcolm Fraser had been sworn in as a caretaker Prime Minister after the dismissal of the Whitlam Government on 11 November 1975.

- ↑ National Archives of Australia, NAA.gov.au Retrieved on 2009-06-09

- ↑ For example "ASX listing for Brain Resource Company Ltd". Company Information. Australian Stock Exchange. http://www.asx.com.au/asx/research/CompanyInfoSearchResults.jsp?searchBy=asxCode&allinfo=on&asxCode=BRC. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- ↑ "Lazard Carnegie Wylie". Carnegie, Wylie & Company. http://www.carnegiewylie.com/template.asp?cid=1.4. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "After office". Australia's PMs - Paul Keating. National Archives of Australia. http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/keating/after-office.aspx. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- ↑ "Books in Print". Booksinprint.seekbooks.com.au. http://booksinprint.seekbooks.com.au/featuredbook1.asp?StoreUrl=booksinprint&bookid=0732910196&db=au. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ↑ "Middle-of-the-road fascists can't compose IR policy". The Australian. 2 May 2007.

- ↑ "The World Today - Keating criticises ALP over compulsory super plan". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2007. http://www.abc.net.au/worldtoday/content/2007/s1863256.htm. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ↑ "Paul Keating relieved John Howard era is over". Herald Sun. 26 November 2007. http://www.news.com.au/heraldsun/story/0,21985,22821565-5013904,00.html. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- ↑ "Keating: Sydney should be the capital". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 May 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17. http://web.archive.org/web/20071017161019/http://abc.net.au/canberra/stories/s1933102.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ↑ Lateline, 7-Jun-2007, Also on YouTube: Youtube.com, YouTube.com, YouTube.com

- ↑ Welch, Dylan (2008-02-13). "Kevin Rudd says sorry". The Sydney Morning Herald. http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/prime-minister-kevin-rudd-made-today-an--historic-one-for-australia/2008/02/13/1202760342960.html. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ↑ Video of speech, part 1Video of speech, part 2

- ↑ Mitchell A Keating's daughter called to testify Sun-Herald October 17 2004

- ↑ Keating promoted culture as something to celebrate, Sydney Morning Herald, 15 September 2009

External links

- Keating's personal website

- "Paul Keating". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/keating/. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- "Paul Keating". National Museum of Australia. http://www.nma.gov.au/education/school_resources/websites_and_interactives/primeministers/paul_keating/. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- Paul Keating Insults Archive

- Paul Keating at the National Film and Sound Archive

- Video - Paul Keating vs John Hewson

- Video - Re: The Great Motion

- Video - Floating the dollar

- Photo - Delivering the annual John Curtin Prime Ministerial Lecture 2009

- Text - 2009 John Curtin Prime Ministerial Lecture

- Painting - Paul Keating

| Parliament of Australia | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by E.J. (Jim) Harrison |

Member for Blaxland 1969 – 1996 |

Succeeded by Michael Hatton |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Rex Patterson |

Minister for Northern Australia 1975 |

Succeeded by Ian Sinclair |

| Preceded by John Howard |

Treasurer of Australia 1983 – 1991 |

Succeeded by Bob Hawke |

| Preceded by Lionel Bowen |

Deputy Prime Minister of Australia 1990 – 1991 |

Succeeded by Brian Howe |

| Preceded by Bob Hawke |

Prime Minister of Australia 1991 – 1996 |

Succeeded by John Howard |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Lionel Bowen |

Deputy Leader of the Australian Labor Party 1990 – 1991 |

Succeeded by Brian Howe |

| Preceded by Bob Hawke |

Leader of the Australian Labor Party 1991 – 1996 |

Succeeded by Kim Beazley |

|

|||||

|

|||||